NYC Water Quality, Stormwater Issues

Red Knots. Photo: David Speiser

New York City’s human population—over eight million people—poses a set of distinct challenges to our wetland ecosystem. To understand these challenges and work toward solutions, it’s important to understand how the City manages its water: both stormwater, or run off from rain and snow, and sanitary sewage—the product of the City’s millions of toilets and sinks. Modern-day New York City has two kinds of systems to handle sanitary sewage and stormwater, depending on one’s neighborhood:

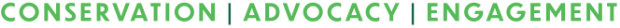

The combined sewer overflow (CSO) system under dry (left) and wet (right) conditions. Graphic: courtesy of NYC Department of Environmental Protection. Click here to view full, enlarged image.

Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO)

First built in the mid-1800s, this older system combines sewage and stormwater in the same pipes, which connect directly to New York Harbor. In dry weather, sanitary sewage all goes to water treatment plants. But when it rains—even as little as one-twentieth of an inch—the system can become overburdened by stormwater, leading to a combination of stormwater and raw, untreated sewage being dumped into our waterways. Today, approximately 60 percent of the City still has a CSO system.

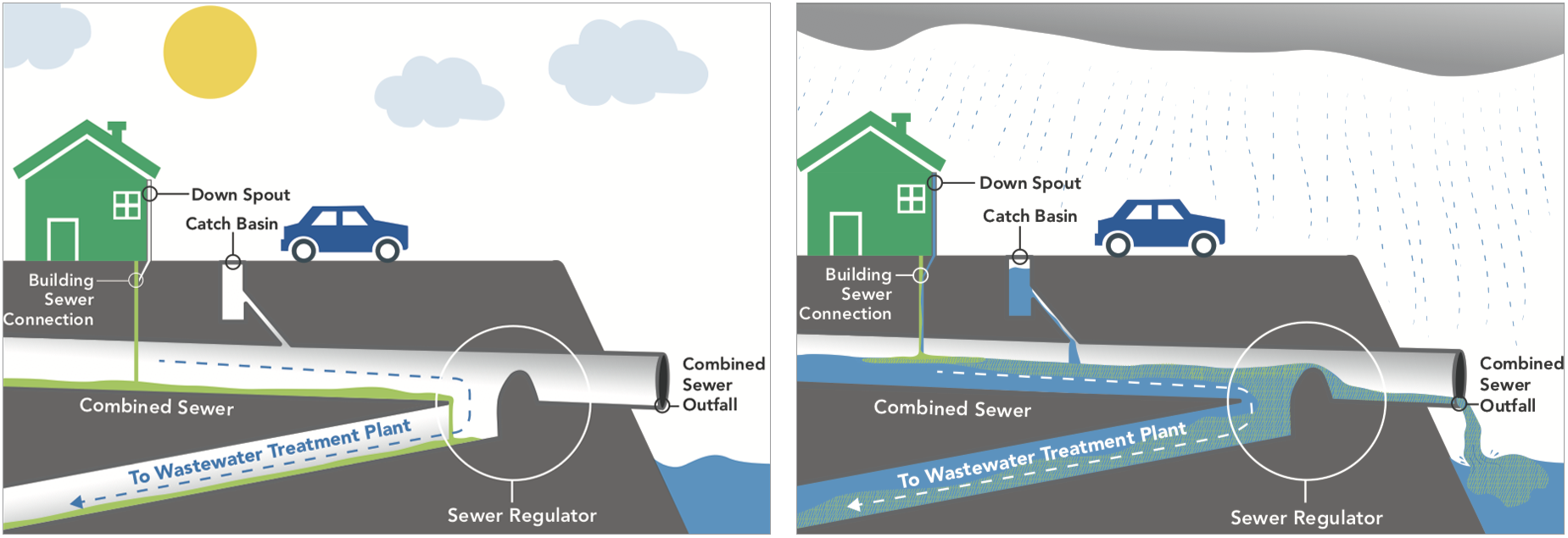

Location of Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems (MS4) in New York City. Graphic: Courtesy of NYC Department of Environmental Protection

Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MSSSS, or “MS4”)

In this more modern set-up, storm sewers and sanitary sewers are separate. As in the CSO system, sanitary sewage is piped to water treatment plants—but with MS4, stormwater is kept separate from sanitary sewage, and conveyed to our waterways.

While MS4 prevents sanitary sewage overflow during storms, in our highly developed landscape, untreated stormwater carries its own dangers. As stormwater flows over streets and other impervious surfaces, it sweeps up pollutants such as oils, chemicals, and litter. This stormwater must be cleansed in other ways, through a system of catch basins and other built infrastructure. As shown on the left, about 30-40 percent of the City now has an MS4 system, largely around Jamaica Bay and on Staten Island. (See an interactive version of this Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System map.)

Eutrophication: The Problem of Too Much Fertilizer

The regular overflow of raw sewage and runoff from paved surfaces has been a serious threat to the health of our wetlands, and to the Jamaica Bay ecosystem in particular. While many chemical contaminants may enter the ecosystem and have adverse effects on its functioning, research over the past few decades has begun pointing to excessive fertilizing nutrients, such as nitrogen, as particularly damaging to marshes. In 2010, the New York City Department of Environmental Protection estimated that almost 40,000 pounds of nitrogen a day poured into Jamaica Bay from four city sewage treatment plants1, making it among the most nitrogen-polluted water bodies in the world.

Extra nitrogen may harm wetland ecosystems in several ways, via the process of eutrophication, or “over fertilizing.” It causes harmful algae blooms that render wetland waters inhospitable to marine life, affecting not only fin- and shellfish populations but also the local and migratory birds that feed on them.

Research published in the journal Nature2 has also shown that elevated levels of chemicals like nitrogen may be contributing directly to the rapid erosion of salt marshes across the globe, via several related mechanisms. In the study, high levels of eutrophying chemicals increased the growth of above-soil plant mass, while decreasing the mass of bank-stabilizing roots—and also increased microbial decomposition of the buried organic matter in the banks of marsh creeks. The combination of these destabilizing changes was associated with the collapse of marsh banks, and the conversion of significant areas of creek-bank marsh to bare mud.

Endangered Rufa Red Knots, Ruddy Turnstones, and Dunlin forage on an eroded fragment of salt marsh in Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, Queens. Photo: Don Riepe

Solutions and Plans for the Future

Excess nitrogen is present in untreated CSOs, but it also often present in treated water. This means that to be effective, solutions to the stormwater problem must involve both improvements to the sewage and stormwater conveyance systems, and improvements to the ability of our water treatment plants to remove nitrogen from treated water.

Through the efforts of environmental groups including the Natural Resources Defense Council and city and state officials, an unprecedented agreement was signed in 2011. Under the agreement, the City and state was to cut in half, by 2020, the amount of nitrogen discharged into the bay from four city sewage treatment plants, pay $100 million to upgrade technology at the plants, and spend an additional $15 million to slow the erosion of the bay’s marsh islands.

The 2011 agreement was a huge step forward for the birds, plants, and animals that depend on clean water in Jamaica Bay. The work continues. In 2018, the City released its New York City Stormwater Management Plan. Through our advocacy work, NYC Bird Alliance continues to support all efforts to upgrade our City’s stormwater system and reduce damaging discharge into the City’s watershed and wetland ecosystem.

New York City is also working to address the problem of CSOs through a variety of responses developed in part by its Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). To prevent sewage overflow events, “Gray” infrastructure (traditional solutions such as sewage treatment plants and storage tanks) are being updated or rebuilt with green alternatives: green roofs, rain barrels, rain gardens, permeable pavement, tree pits with below-grade water catchments, and bioswales that catch and store rainwater. Read more about NYC Bird Alliance’s work with green infrastructure.

Learn More about New York City’s Stormwater Management

- Learn more about Combined Sewer Overflows and ways to prevent them.

- View the NYC Stormwater Management Program (PDF), revised in 2019.

- Visit Stormwater Infrastructure Matters, a citywide coalition dedicated to establishing sustainable stormwater management practices in the City.

- Visit Riverkeeper’s informative page on Combined Sewer Overflows.

Citations

- NYC Department of Environmental Protection, Public Affairs, 2010. DEP Launches New Measures to Improve Overall Ecology of Jamaica Bay.

- Deegan, L.A., Johnson, D.S., Warren, R.S., Peterson, B.J., Fleeger, J.W., Fagherazzi, S. and Wollheim, W.M., 2012. Coastal eutrophication as a driver of salt marsh loss. Nature, 490(7420), pp.388-392.